A Short History of Sudbrook Park

by Melanie Anson

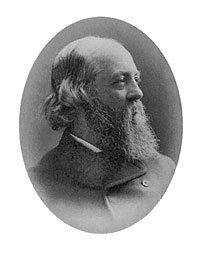

Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the founder of landscape architecture in America, designed Sudbrook in 1889. His roads of continuous curvature were a graceful work of art compared to the rectangular grid pattern that predominated at that time.

In the 1850s, prominent Baltimorean James Howard McHenry (1820-1888), grandson of the famous statesman James McHenry and the Revolutionary War hero Col. John Eager Howard, purchased over 850 acres of land in Pikesville and named his estate "Sudbrook." At that time, the only way to travel the eight miles into Baltimore City was by horse and carriage over bumpy dirt roads, a problem McHenry eventually solved by securing train service through his property in the 1870s. With transportation in place, McHenry actively sought to develop his Sudbrook estate as a "suburban village," a concept in its earliest infancy.

In 1876, McHenry first contacted Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. to design a suburban community on his Sudbrook estate. Olmsted had gained fame, with Calvert Vaux, for the co-design of New York City's Central Park. His renown as America's preeminent landscape architect grew with his designs for other parks, college campuses, the grounds of the U. S. Capitol and in 1869, his plan for the suburban village of Riverside outside Chicago. But McHenry's plans met several obstacles. He suffered repeated financial setbacks and was unable to bring his dream to fruition before he died in 1888.

Shortly after McHenry's death, a group of Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore investors formed The Sudbrook Company, purchased 204-acres from the McHenry estate and by August 1889, had a design for a suburban village designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., who was assisted by his adopted son and partner, John Charles Olmsted, also a notable landscape architect. Col. George E. Waring, Jr., the most distinguished sanitary engineer of that period (who had worked with Olmsted on Central Park and Riverside), designed highly advanced underground storm drainage and sewer systems for the Sudbrook community. Hugh Bond, a prominent Baltimorean, was President of The Sudbrook Company and Eugene Blackford, who had been a friend of McHenry's, was hired to oversee building and to manage the new community. Blackford staked out Olmsted's curvilinear roads himself; his tireless efforts insured that the developing community conformed with Olmsted's vision.

Sudbrook Park opened in the spring of 1890 with its entranceway bridge, a train station, a hotel, and nine sample "cottages." Summering spring through fall in Sudbrook was highly popular with Baltimore's social set from the community's inception. The Park offered its occupants the advantages of a high elevation in a picturesque wooded section far from the heat and annoyances of the city and in close proximity to the Western Maryland Railroad, which ran several trains a day. But the sale of property for year-round residences (as intended by Olmsted and The Sudbrook Company) was a hard sell; most Baltimoreans could not be convinced to live year-round so far from the city. Property sales languished. Blackford's death in 1908 was a severe loss and by 1910, The Sudbrook Company withdrew from active management. Residents formed The Sudbrook Park Improvement Association after Blackford's death to provide some direction. By 1930 there were about 50 homes in Sudbrook Park.

Sudbrook Park grew to over 500 homes during the second wave of suburbanization, from 1939 to the early 1950s, when hundreds of brick Neo-Colonial and Cape Cod homes were built to accommodate Baltimoreans with automobiles. The new developers retained much of the Olmsted ambiance-preserving the community's mature trees, curving roads and deep setbacks so that the newer homes blended well. Old and new residents alike made trees and open space preservation a paramount goal.

As early as the 1940s, state planners quietly targeted the heavily treed triangles and open spaces which Olmsted situated at the entranceway as a prime location for a six-lane expressway which later included a rapid transit line in the median. This federally-funded project, which would have demolished the Olmsted-design, was defeated after a long community fight when a portion of Sudbrook Park was designated a National Register Historic District in 1973. From 1978 until the early 1980s, the community again rallied to fight similarly devastating plans to route the transit line in an "open cut" along the old expressway route through Sudbrook; this plan would have necessitated replacing the narrow entranceway bridge with a new one 4-lanes wide and adding a second bridge above the open cut. As a compromise, the transit line was placed in a "cut and cover" tunnel through the entranceway area. Although many towering trees were lost, the bridge was saved. Had residents not waged and won these battles, Olmsted's historic design for Sudbrook (which is the only Maryland community designed by Olmsted, Sr. and one of only three remaining Olmsted Sr. residential communities in the country) would have been destroyed.

Sudbrook Park continues to work to protect its Olmsted legacy and preserve its historic character.

OLMSTED DESIGN PRINCIPLES

Sudbrook Park is an excellent example of key Olmsted residential design principles:

The community has a distinct entranceway - an approach road leading to a narrow bridge after which five roads fan out through the neighborhood.

Curvilinear roads, which provide a more tranquil and leisurely visual experience.

Open green spaces and "triangles" at the entranceway and other intersections - still used for gatherings by residents as Olmsted intended.

Majestic hardwood trees along the road and in interior yards, as well as lush vegetation to create a naturalistic beauty.

The inclusion of smaller as well as larger lots.

Sixteen deed restrictions, the most detailed Olmsted had done, to protect the visual quality of his master plan, preserve the residential character of the neighborhood and insure acceptable sanitation practices. These restrictions were innovative, early versions of zoning regulations.

OLMSTED-RELATED LINKS

Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

National Association for Olmsted Parks

Friends of Maryland's Olmsted Parks and Landscapes

HISTORIC DISTRICT STATUS

Sudbrook Park has within its boundaries a National Register Historic District and Baltimore County Historic Districts.

In 1973, the oldest section of Sudbrook Park, including the entranceway area, was listed on the National Register of Historic Sites and Places. A National Register District designation recognizes the historic importance and contribution of the community to United States history. National Register designation carries no homeowner restrictions; it does require regulatory review for any federally-funded project that might impact an historic district.

In 1993, a portion of Sudbrook Park including and slightly larger than the National Register District was recognized as a Baltimore County Historic District, with expansions in 1995 (600 block of Cliveden Road) and 1999 (900 block of Adana Road). A Baltimore County Historic District designation recognizes the value of the community to the county's history and also places review requirements on exterior changes to any property within the county district, to insure that such changes comply with The Secretary of the Interior's Standards.

NATIONAL HISTORIC LINKS

National Trust for Historic Preservation

National Register of Historic Places

National Park Service's Preservation Briefs

The source for this information is:

Anson, Melanie D. Olmsted's Sudbrook: The Making of a Community. Sudbrook Park, Inc., 1997.

If you are interested in purchasing the book, please contact treasurer@sudbrookpark.org.